The Bright Lights and Big City of Beatitude

LARRY CLOSS

I’m alone at Think Coffee on Bleecker and Bowery—yeah, the original and still the best—and that good-looking guy from that Netflix series sits right next to me. He’s wearing a black hoodie, dark stressed jeans and work boots and he seems instantly at home yet somehow out of place. For a moment, I find myself wondering why he’s not sporting a suit. And then I realize: we are in an East Village coffee joint and he is just another New Yorker, craving caffeine, just like me.

Only in New York does the line between fact and fiction so easily blur. New York is as much a set as it is a city, a charismatic, cinematic mise-en-scène that everyone in the world has visited—even if they’ve never been here—through books, movies and TV. Set a fictional story in New York and you instantly add a sense of verisimilitude. I was fortunate to be able to set my novel, Beatitude, in New York, to have my protagonists’ story play out beneath the bright lights of the big city that’s instantly familiar yet awe-inspiring to everyone on the planet. It helped to be a New Yorker, of course, although I wasn’t always one.

When I first moved to New York and I was looking for an apartment, I called a broker about a listing. He told me to meet him in front of Citarella Fish on the Upper West Side.

“Where’s that?” I asked.

“Citarella Fish!” he yelled into the phone, as if saying it louder would somehow clarify its location, as if there was no way I couldn’t know where it was.

But I didn’t.

“You don’t know where Citarella Fish is?” he asked incredulously.

“Sorry,” I said. “I’ve never heard of it.”

“What? It’s next to Fairway!”

I’d never heard of Fairway, either.

“You’re not a New Yorker, are you?”

Twenty years later, Fairway is my neighborhood market. And I am a New Yorker. I walk fast. I talk fast. I don’t wait for traffic lights. I work out. I order out. I stay out of Times Square. And Soho. I can hear the first three notes of “Somewhere” from West Side Story in the metallic screech of a subway train’s wheels as it pulls out of a station. When I go for a run in the park, it’s Central Park. When a friend walks across a bridge on her way to work, it’s the Brooklyn Bridge. When my sister calls and comments on all the noise in my apartment, I vaguely remember being bothered by the sound of the traffic just beyond my windows but haven’t heard it for years. I know where Citarella Fish is, but I would never berate someone for not knowing.

As a Metro Card-carrying New Yorker, I was intimate enough with the city to make it one of the main characters in Beatitude. New York shares every scene with Harry, Jay and Zahra, from the New York Public Library, Gotham Book Mart and Rudy’s Bar & Grill to Café Dante, the Bitter End and Nuyorican Poets Café. But the New York of 1995, when Beatitude takes place, is gone. The Gotham Book Mart, gone. Chicago Blues, gone. Star Burger, gone. Subway tokens, gone. The Tytell Typewriter Company, Martin Tytell and Allen Ginsberg, gone, gone and gone. The run-down red-brick row house where Jack Kerouac wrote the first draft of On the Road on a 120-foot scroll, not gone but completely rehabbed. All a part of history now, a New York that was but no longer is, existing only in the memories of those who were there.

Harry and Jay were there. One reviewer described the dimensions of their friendship as “epic,” a quality conjured by their supreme loyalty to one another but no doubt enhanced by the fact that their story unfolds in the near-otherworldly dimensions of New York. The city’s influence on my life, my work and my writing has been incalculable. Epic, even. New York is beat and beatific. It’s a concrete jungle with streets that make you feel brand new. It’s the stuff of song. It’s the stuff of dreams. It’s the stuff of Beatitude.

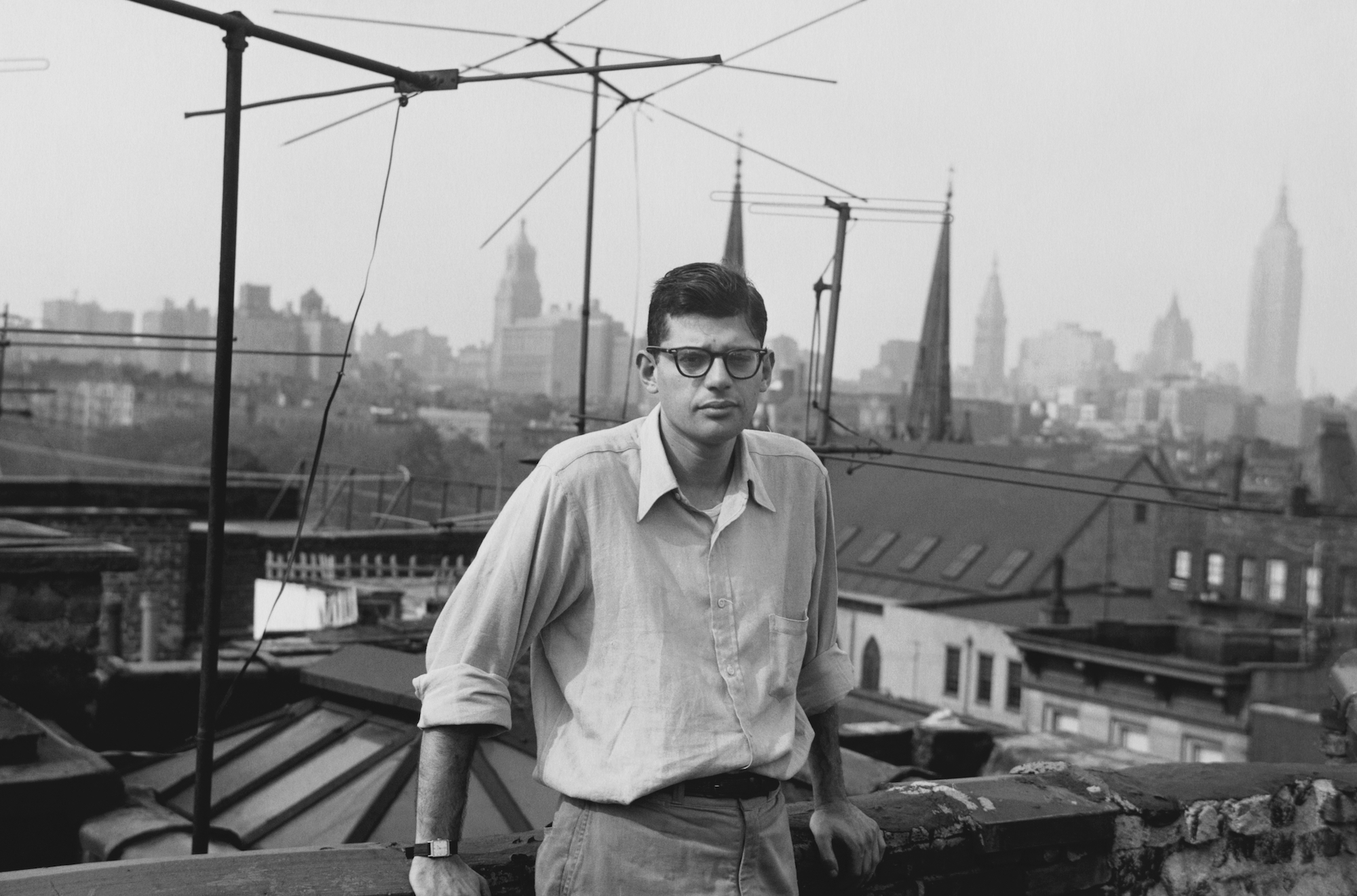

Photo: Allen Ginsberg – New York City, Fall 1953; Myself seen by William Burroughs, my new-bought Kodak Retina from Bowery hock-shop in his hand, our apartment roof Lower East Side between Avenues B & C, Tompkins Park trees under new antennae, Kerouac, Corso and Alan Ansen visited, The Subterraneans records much of the scene, Burroughs & I worked editing manuscripts he’d sent me as letters from Mexico & South America, the neighborhood heavily Polish & Ukrainian, some artists, junkies & medical students, rent only 1/4 of my $120 monthly wage as newspaper copyboy. Fall 1953.